How to Decide What to Show in a Game Trailer (and in what order to put it)

How do you decide what game footage to show in your trailer, and figure out what order to show it? This is a difficult problem in the context of the infinite possibility space of capturing footage. For the purposes of a game trailer producer, a game is basically footage generating software. How do you decide the type of footage the trailer needs? I create the outlines for my trailers by thinking of the parts of a game in layers. First I build the foundation, then once that's set, I can add the layers which flesh out the game but are less essential.

Here are the layers of a trailer, and how I use them to create the first outline for my trailers:

Story & Player Verbs

NPCs, enemies, objects, weapons, items

Biomes, level art, color palettes

What's the Story?

Story and player verbs are very different things, and yet they're very hard to separate in a game trailer because the player verbs (the actions you can perform as the player like walking, running, jumping, flipping switches, talking, etc.) are the means by which the story is told. If you, the player, do not do any of those things, the story does not progress. But at the same time, there are story trailers and gameplay trailers which focus exclusively on one or the other. Depending on the direction of the trailer, one is the foundation, and the other gets sprinkled on top.

If a game has about equal focus on story and gameplay I start with story. For example, for the trailer I made for Desta: The Memories Between, this is the story:

Desta is having dreams of their hometown they haven't been to in two years since their father passed away

Desta doesn't have a strong relationship with their mother

Their father would throw a ball around with them to help work through problems

Desta returns home to confront and reconnect with friends

As with any narrative driven game, there were dozens of scenes and lines of dialogue to choose from. Narrative games often have hundreds or several thousands of lines! With only 90 seconds or fewer it's super easy to NOT tell a story well in a trailer. Every line has to communicate something about the story AND should create a throughline from beginning to end. Scattershot stories leave the audience confused and disoriented.

The more your trailer’s chosen story bits can align with what happens in the game’s story or gameplay, the easier it is to intercut

The trick is to find the broad strokes of the story. The parts of the story which create your one-sentence pitch. Most lines of dialogue are going to be small moments like: "Luke, if they have a translator droid, make sure it speaks Bocce!" Those lines require a lot of context to understand, and even when understood don't illustrate much of the larger story. If a line is too specific to one scene, it's a lot harder to then incorporate player verbs which intercut well.

If I used a line where Desta said something like: "Hey, remember when rode our skateboards through the mall and the security guards chased us?" I'd have a very difficult time showing some player actions if this exact scenario didn't exist in the game. But, a line like: "I can't keep running" can be paired with a shot that shows Desta retreating in the game (at 1:11 in the trailer).

For the purposes of my outline I write out the core, broad story beats. I do this by making a massive timeline with broken down dialogue and story beats and distill it to the absolute essentials. It's super hard to just pick out only the essential story beats. It's much easier to start with too much and whittle it down. The process is a lot of looking for redundancies, and asking myself if the story would still hold up if a line was removed.

If the trailer was ONLY this story with cutscenes, I don't think it would be doing a great job as a game trailer (maybe just an announce trailer). This is a trailer for a game, so next we need to layer on the player verbs.

When you have cutscenes it’s very easy to just lean on them in a trailer, but it’s more valuable to show how it connects to gameplay.

What Do I Do in the Game?

A lot of game trailers will actually start here, because the story isn't essential to the core of the game. For example, Spelunky 2 has a story, but it's easy to skip and just focus on playing the game. Since game trailers are part story and part instructional video for how the gameplay works, it makes sense to start your outline here for "game-y" games.

Once again, you can find this player verb structure by thinking of your one-sentence pitch and what you'd say to someone face-to-face if they want to hear more. If I reverse engineer the player verbs the Desta trailer, here's how it goes:

There's an isometric grid-based playing field you walk around and a ball you pick up

You throw the ball around the field

The ball can ricochet and hit other people

The other people throw balls at you too

You can bounce the ball around corners to hit enemies

The characters have special abilities that increase their tactical options and can give them the advantage

You can pass the ball between your team members

You level up your skills and gain new abilities

Enemies also have special abilities

You turn enemies into friends and create custom teams

(Assortment of different cool gameplay stuff in a montage)

This very basic gameplay scenario illustrates the core game mechanic. I chose this too because I thought the crystal looked like a grave stone and would match with the Father’s memorial story beat.

If I were to write out this list of verbs and actions in plain speech it would be something like this:

"Desta is an isometric tactical turn-based ball throwing game where you defeat enemies by picking up a ball on the field and throwing it at them. There are a finite number of balls, so you and the enemies need to plan your moves carefully to win each level. The ball can be bounced off walls and enemies, which creates unique tactical options. There are also special character abilities that mix up the gameplay, and as you play you level them up while also building up your roster of characters who you can use to make customized teams. Enemies will also have unique abilities and powers which will make them more difficult to defeat."

To get to this structure, I looked at the game loop and broke it down into the different stages as you learn how to play the game, how it adds on mechanics, and repeats. Starting in chronological order is the easiest way to plan out what you show in a game trailer. A lot of game trailers would do well to keep everything in order, because games are typically designed in a way to teach people how to play starting with the basics, adding complications, and repeating in escalating cycles (perfect for a trailer!)

To plan out your player verb-based structure, write out what the player learns in order it occurs. For some games it might be too boring to show every step. This goes especially for sequels where the fundamental game mechanics are known before the trailer starts playing (You don't need to teach people how a Call of Duty game plays), or games in a very well known genre. But a long reel of the game mechanics in order is a good place to start and then prune out the boring or redundant bits.

Notice what's NOT in this outline. None of this says anything about what biomes the shots are captured in, what enemies Desta fights, or what abilities get used. At this stage I'm just focusing on the essentials of what you do in the game because these are the fundamentals. Everything else that follows will provide flavor and variety.

This shot showing the ricochet mechanic builds upon the basic throwing idea

Objects & Items

After I plan out the story and player verbs, it's time to focus on the things the player interacts with. For example, which enemies does the player fight? What objects do they pick up? What power ups do they use? The philosophy of this process is starting with the big categories and working on the details later. You might not work well in this way, but for years this is what's worked for me.

How do you plan out this phase? For Spelunky 2 I wrote down all the new enemy types and crossed out anything I didn't want to spoil. Then I decided what order I wanted to show them based on how exciting and interesting they were. For example, an enemy type like the Mole is very game changing, but not visually very flashy. The robots I saved for later because they explode when you jump on them. I also used this process for the different items and power-ups. For example, I saved the flashy teleporter backpack for the very end of the trailer and put the less flashy crossbow in the middle.

This is a good time to note sometimes items and enemies actually dictate what player verbs you show, so this section and the last aren't always mutually exclusive. Now that we know the basic story, what the player does in each section, and what things they interact with, we move onto the final layer.

This section started as “Desta uses an ability.” I later chose the grappling hook because it’s easy to understand. I also chose this level and enemy because their shield ability necessitated getting behind them.

Paint & Decorations

The last step of the process is where I worry about the environments, biomes, and color palettes. Ideally, the trailer has a good variety of colors to keep things looking fresh. For example, if every single shot is in a forest level (and that's just one of many biomes in the game) then the game will look small in scope and dull. Again, the biomes can often be linked to enemy types, weapons, power-ups, and things the player interacts with. So some things will necessarily have to be planned out in an earlier phase, but I find oftentimes worrying about the environments and color palettes can be saved for last.

At the very least, before I get to this phase I will look at how many color palettes are shown in the trailer, and if there needs to be a burst of color or at least a contrasting color to keep things visually fresh. What I DON'T do is decide on the levels first, start the trailer with the player running through a montage of environments and put it in the beginning of the trailer. My step of writing out the pitch and the player verbs is what prevents me from doing that. If I was giving a verbal pitch, I wouldn't start with: "In this game you run through a variety of environments, a forest, a volcano, cave, an ice cave..." so it doesn't make sense to start a trailer that way (unless it was a map DLC, or update trailer)

If you want to get really fancy, you can consider the Pixar technique of creating a color script where the colors change according to the story arc. I could see this working in a trailer, but since trailers tend to change colors just to keep the eye engaged, trying this process might not be the best. At the very least, looking at the color palettes across the trailer can be very handy if you don't know if your trailer has enough color variety.

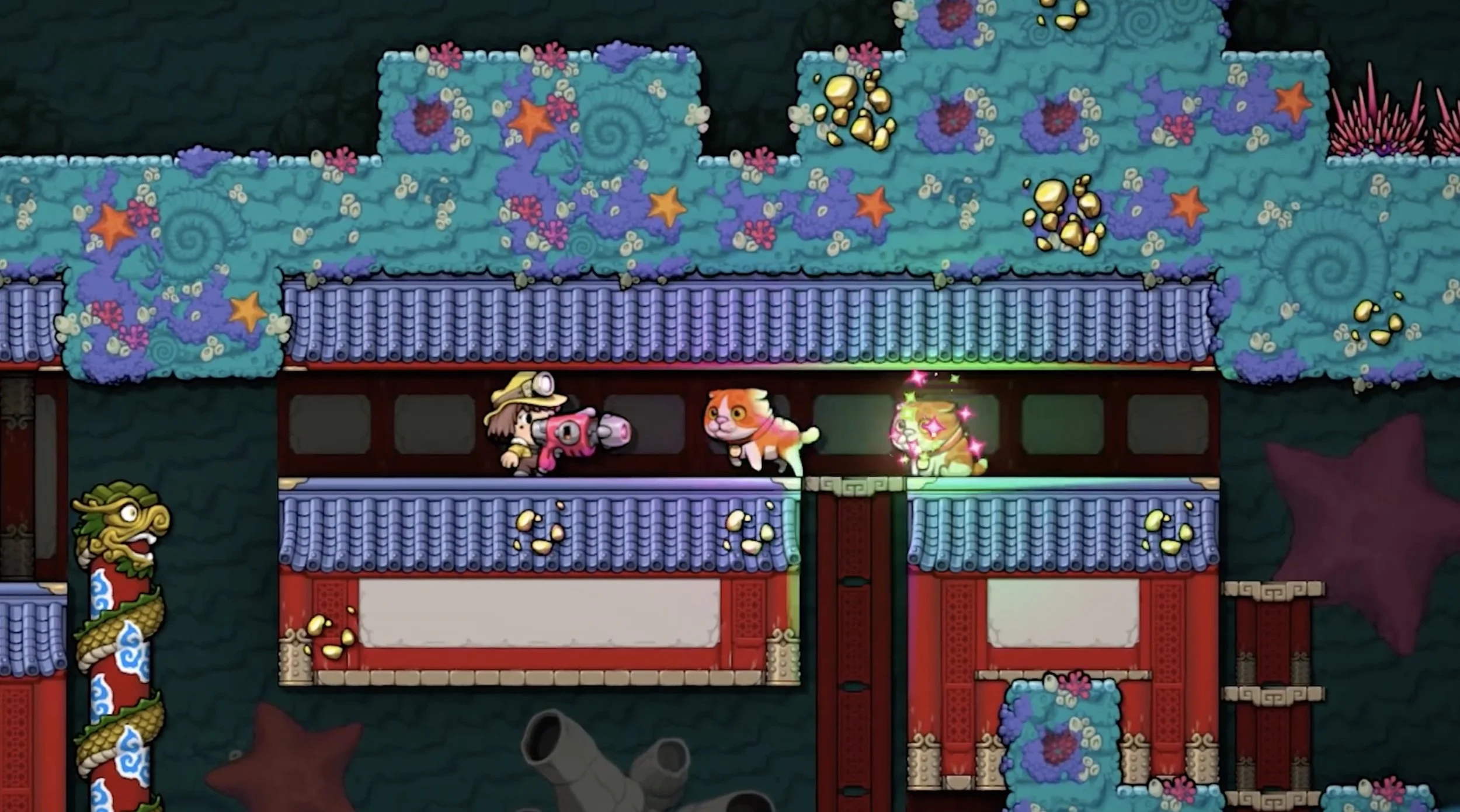

I put this shot in the middle of the Spelunky 2 gameplay trailer to give the trailer’s color palette a little jolt (though I could’ve used the clone gun on a cat anywhere in the game)

Conclusion

If I may extend my analogy a bit more. For the purposes of a game trailer:

Story & Player Verbs are the foundational materials like cement, brick, wood, and metal.

What the player interacts with are the things that go in the house.

Biomes, level art and color palette are like the paint and decorations.

You can't build a house out of paint, or the things that go inside of the house. Okay, maybe SOMEONE can, but it's going to be much more difficult and less compelling. Again, this process may not work for you at all, but it's best for me to work in this order because it helps me compartmentalize the game's components, and have somewhere to start (and finish).